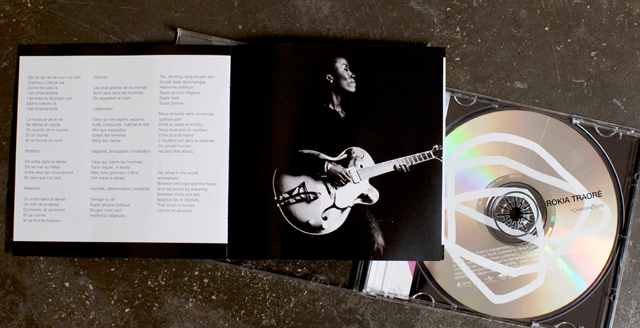

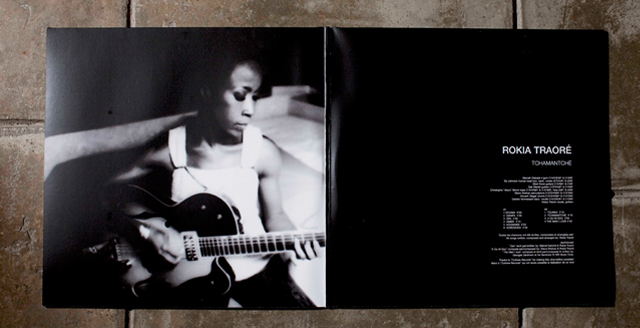

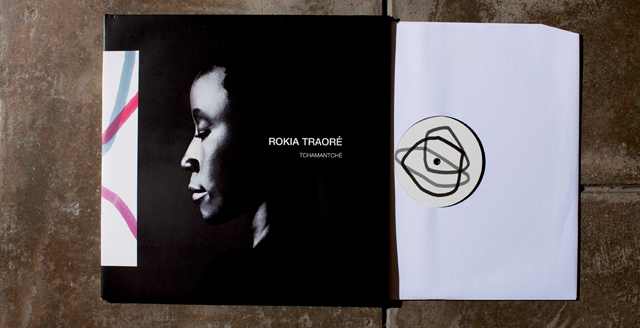

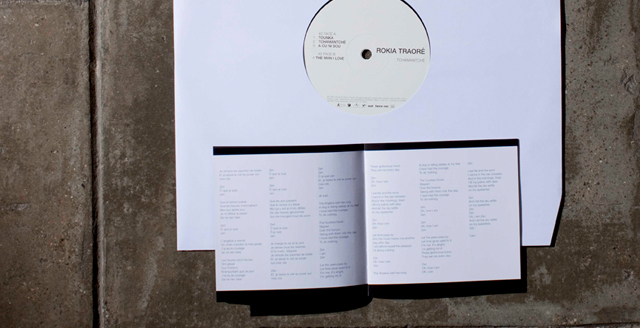

(Outhere Records OH011 / release date: 11.11.2008 (GAS))

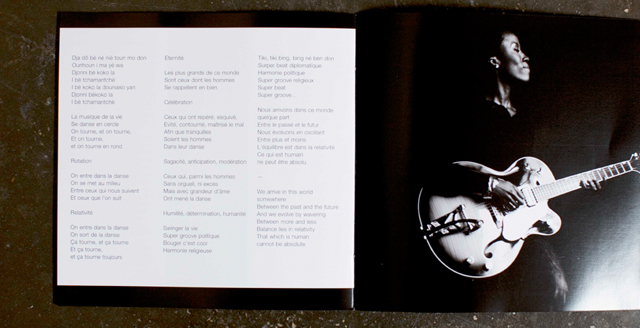

It all started with a sound inside Rokia Traore’s head. The most adventurous singer-songwriter in Africa knew that she wanted to create a new musical style that was “more modern, but still African, something more blues and rock than my folk guitar”. Then she heard an old Gretsch, the classic electric guitar so beloved by American rockabilly bands back in the Fifties and Sixties, and played by everyone from Chet Atkins to George Harrison. That was the sound she had been looking for, and it has helped to bring a fresh and startling new dimension to her exquisite and adventurous songs.

This may be an African album, but it sounds nothing like most ‘world music’ records, and has little in common with work of Rokia’s great Malian compatriots like Salif Keita or Oumou Sangare “who are amazing, but I’m not a Malian traditional singer”. It will appeal to blues fans, though it’s not just a blues album, and it will appeal to fans to sophisticated contemporary rock, though Rokia’s always thoughtful and intriguing lyrics are mostly sung in Bambara, one of the Malian languages, with just two in French. “I can’t say what style I am”, she admitted. “But I just love music”.

The result is an album that constantly surprises. The only track not written by Rokia is a startling re-working of the Billie Holiday classic The Man I Love, which starts as a slow, bluesy track in which Rokia demonstrates her delicately brooding, intimate vocals (in English), and then speeds up to develop into an extraordinary African scat work-out. The backing includes both Gretsch guitar and the n’goni, the tiny, harsh-edged West African lute that has always been an integral part of her sound.

Elsewhere, many of the songs are built around laid-back, sturdy and slinky grooves, and Rokia sings with a new maturity, range and quiet confidence. The backing is often sparse, but always original, with sections where another classic guitar, the Silvertone, is matched against subtle percussion effects provided by human beat box and hip hop star, Sly Johnson, or where the n’goni is played alongside the Western classical harp.

That song would be revived once again last year, when Rokia was involved in another experimental project, writing and performing a new work for the New Crowned Hope festival that was staged by the maverick director Peter Sellars, with shows in both Vienna and London to celebrate the 250th anniversary of Mozart’s birthday. She responded, in typically brave fashion, by transforming the whole idea by presenting a work in which Mozart was born as a griot, a hereditary musician, back in the time of the great Thirteenth century ruler Soundiata Keita, whose Mande empire was centred in what is now Mali. The music involved anything from West African instruments to guitar and bass, violin and clarinet.

Now, at last, there’s a new album that marks the latest stage in a career that has transformed Western conceptions of African music. “I wanted a new beginning”, Rokia explained. “As if I was someone just starting their career. I love new experiments and trying to do things differently. I wanted to take that Gretsch sound and do everything in a different way”. The result is surely one of the albums of the year.